Results

The responses to the three

questionnaires from Kuhlthau’s SLIM toolkit were varied and occasionally

unexpected. A sample of 10 students was taken from the original 24. Four

students were unable to complete all 3 questionnaires due to absence. The

sample was chosen on the basis of all three questionnaires being completed

fully. Every second student was chosen on an alphabetical basis. All completed questionnaires were, however

checked for consistency of themes and content. To preserve anonymity, students

are referred to as A, B, C etc.

Figure 1: Question 1 Number of facts reported by each student for each questionnaire

Figure 1: Question 1 Number of facts reported by each student for each questionnaire

The students had received their

task sheets and completed one lesson on the topic before answering the first

questionnaire. During this initial lesson they had completed an online survey

which was developed to help anyone determine their “ecological footprint”. This

exercise had given them some idea of the topic and task requirements before

they completed Questionnaire 1.

Their responses were qualitatively

graded as facts, explanations or conclusions as explained in the SLIM toolkit. This question required students to report what they know about

their topic with the expectation being that the number of facts would increase with

subsequent questionnaires, as the students started researching their topic. Of

the 10 sample students examined, this trend was noticed to a certain extent

especially with students A, E, F, G and I. See Figure 1 below.

When taking all the students

results into account across all three questionnaires we see that “Facts”

represent the greatest proportion of the three types of responses.

A reason for the greater number of

facts, rather than explanations and conclusions being reported in

Questionnaires 1 and 2 could be that students were not encouraged to write

their replies in full sentences (as recommended in the SLIM toolkit), and they

did not receive sufficient time to complete the questionnaire. During

Questionnaire 3 many of those statements were written in response to Questions

6. I have corrected my results taking those statements in account later in this

report.

The changes noted between the

questionnaires for the number of facts, explanations and conclusions reported

for the sample of 10 students can be seen in the following graph.

Figure 3: The number of facts, explanations and conclusions for the student sample across all three questionnaires

An increase in the amount of facts

was reported in Questionnaire 2 followed by a slight decrease for Questionnaire

3. The student answers for Questionnaire

1 commonly centred on a generalised conception of their ecological

footprint. The same question was asked

in Questionnaires 2 and 3, with answers becoming progressively more specific to

the students’ chosen research questions. My observation was that although the

actual number of facts decreased from Questionnaire 2 to 3; the quality, detail

and specificity of each student’s answers improved with each subsequent

questionnaire. This is not taken into account in the graphical representations

but can be observed in the following table.

For some students the number of

facts supplied in Questionnaire 3 decreased. This may be explained by students feeling reluctant

to repeat information supplied in previous questionnaires. In many cases it was also noted that students

understood Question 1 and Question 6 of Questionnaire 3 to be referring to the

same thing. Many of the statements that should have appeared in Question 1 of

the last questionnaire actually appeared in Question 6; skewing the results and

making it appear that fewer facts were reported in Questionnaire 3 than

actually were. The following table

illustrates excerpts from student statements showing how answers to Question 6

would have been better placed as answers for Question 1. The reason for this

was they were statements about the topic rather than statements reflecting the

information literacy experience gained whilst undertaking an inquiry task.

Table 2: Examples of Question 6 Questionnaire 3 responses which would have been better suited under Question 1

Table

2 shows us that the results for fact, explanations and conclusions would have

changed significantly had Question 6’s statements been taken into account where

appropriate. As explained under

“Recommendations”; when repeating an inquiry unit of this type or administering

the “SLIM” questionnaires again I would be very careful to explain the

distinction between comments on knowledge of the topic vs comments on

information literacy gained during the inquiry task.

If

Figure 3 is corrected using Question 6’s replies where appropriate, the

following graph is obtained.

Figure 4: Answers to Question 1 corrected using answers to Question 6 of Questionnaire 3 where appropriate

Here

we see a steady yet significant increase in the number of facts reported during

the course of the inquiry task. The number of explanations decreases fairly

dramatically in Questionnaire 2 and then increases again in the last

questionnaire, almost reaching the initial questionnaire’s level. Bloom’s

revised taxonomy describes conclusions as a higher order thinking task

comparable to evaluating. As an inquiry task progresses you would expect more

of these higher order statements. The number of conclusions drops to zero in

Questionnaire 2 and then doubles for the last questionnaire. A reason for the

decrease and then increase in explanations and conclusions would most likely be

that they students were in the “exploration phase” of Kuhlthau’s ISP. This is described as the most difficult stage

of the ISP with students becoming frustrated and discouraged. It is at this

stage that students most require assistance from their instructional team of

teachers and librarian. (Kuhlthau 2007) The noticeable increase in explanations

and conclusions in Questionnaire 3 demonstrates that these students were able

to benefit significantly from intervention strategies provided by the

instructional team. These interventions consisted of; advice on search

strategies when using the internet, how to determine whether a site is reliable

or biased, how to reference and keep notes for a bibliography, using Word for a

bibliography, how to do a “Survey Monkey” to get primary data and how to use

proforma sentence structure devise to verbally analyse graphical data. During

conversations with students it was also possible for me to assist with

misunderstandings of words; for instance, the meanings and implications of

“primary and secondary data”. Many of these interventions consisted of a one-on-one

scaffolding as suggested by Vygotsky in his “Zone of Proximal Development" (Kuhlthau, 2007)

Figure 5: Vygotsky's Zone of Proximal Development. Photo credit:

The students’ self reported “perceived” knowledge (Question 3) uses a qualitative scoring rubric of 0= Nothing 1= Not much 2= Quite a bit and 3= A great deal. The question is “How much do you know about this topic?” When results are compared across the three questionnaires we see that in the first questionnaire only 2 students answered “nothing” and the majority of students answered “not much”. No student felt confident enough at this stage to answer “A great deal”. This is to be expected when students have recently been introduced to a new task.

The students’ self reported “perceived” knowledge (Question 3) uses a qualitative scoring rubric of 0= Nothing 1= Not much 2= Quite a bit and 3= A great deal. The question is “How much do you know about this topic?” When results are compared across the three questionnaires we see that in the first questionnaire only 2 students answered “nothing” and the majority of students answered “not much”. No student felt confident enough at this stage to answer “A great deal”. This is to be expected when students have recently been introduced to a new task.

When the same question was asked a

few weeks later no students answered that they did not know anything, but at

this stage of the task no student was confident enough in their knowledge to

answer “A great deal” either.

Figure 7: Perceived knowledge Questionnaire 2

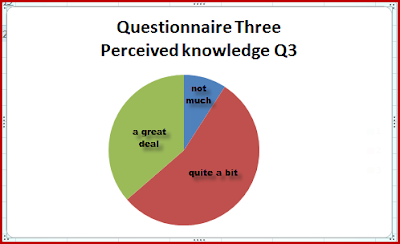

By the end of the task when students had given

their presentations, significantly more of them were confident enough in their

knowledge to answer “A great deal” and only two answered “Not much”, with no

student answering “Nothing”.

Figure 8: Perceived knowledge Questionnaire 3

Using the 10 student sample and

making a comparison between answers to questions 1, 2 and 3 will demonstrate

the correlation between perceived knowledge, interest and illustrated

knowledge. Illustrated knowledge was

corrected proportionally so that all three parameters could be compared using a

scale from 0 to 3 where 0=nothing and 3=a great deal. Therefore, “Perceived

knowledge” as measured by Question 3: “How much do you know about this topic?”;

“Interest” as measured by Question 2: “How interested are you in this topic?” and

“Illustrated knowledge” as measured by counting the number of factual,

explanatory and conclusive statements made for Question 1: “Write down what you

know about your topic” were compared. A

strong correlation between these three parameters for the majority of students

is demonstrated, especially for Questionnaire 3. The steady increase in the length of the bars

in the graph below demonstrates that the amount measured from questionnaire to

questionnaire increases and is noticeably greater for questionnaire 3. This

illustrates that these students, on the whole, are reasonably aware of their

own strengths and weaknesses and this correlation lends credibility to their

self reported insights.

Figure 9: Correlation between perceived knowledge, interest and illustrated knowledge

The same information was then

manipulated to show each student’s progression. It can be seen that most students

experienced a marked improvement between Questionnaires 1 and 3. The graph also

shows that many students either stayed the same from Questionnaires 1 to 2 or

may even have declined slightly. This may seem counterintuitive, with the

reader expecting the results to show a steady improvement in all categories as

the task progresses. However the decline in interest can be explained by Kuhlthau’s

stages of the ISP [provide a link here], as the second questionnaire would have

been administered when most students were experiencing the “exploration” stage

of their task. Common emotions felt during this stage would be confusion,

frustration and doubt; this shows up as a decline in interest in the topic. Only

students E and F experienced an improvement in interest in their topic from Questionnaires

1 to 2.

Figure 9: Correlation between perceived knowledge, interest and illustrated knowledge

Question

4 served the purpose of finding out what students find easy when they do

research. I categorised the information literacy standards achieved by the

students as:

·

Develop research question/s

·

Access information

·

Determine accuracy

·

Organisation skills

·

Understanding and applying information

·

Communication skills

·

Improvement strategies

·

Acknowledging sources

·

Technology skills

The categories correlate to those of the Standards for the 21st century learner (American Association of School Librarians).

Most students were able to develop appropriate questions and search strategies leading them to source information on the topics that interested them the most. After the second questionnaire students were much more comfortable locating relevant information. This can be attributed intervention strategies and training from their teacher and librarian to assist students with the development of focus questions, expert search strategies and evaluating the credibility of their sources.

The following excerpts are of typical student responses for tasks they found easy when doing research;

· “Finding valuable information from reliable websites was quite easy because Public transit websites have valuable information and so did the state government.” Student A

· “I find it easy to get the information in my head and understand it. I find it easier to get information on the internet and newspapers. I find it easy when I get direct quotes from a person to use for evidence”. Student C

· “Thinking back to my research project, I found finding credible book resources easy through using the school library and the BCC library, I also found finding internet resources easy as well as organising the research. Working out if information is credible.” Student E.

· “I found it easy to pick out the information that was relevant and what was not which helped me a great deal when writing my AVD [annotated visual display]. I also found it easy to find the correct information when I researched more specific terms” Student I

By the end of the inquiry task many students reported that selecting and narrowing down heaps of information for their AVD was difficult. The literacy skills skills of organising and understanding content well enough to summarise it and phrase it succinctly were needed to create the AVD which was a A3 sheet of paper with both information and illustrations. Typical comments were:

Student A. “I found putting the information into words

and finding the right pictures quite difficult.

Student E. “...picking out appropriate information from

websites, creating the annotated visual display as well as working out which

questions I should find research for”

Student I . “...difficult

to know what exactly to put on my AVD and to find enough visuals so that my AVD

was 60% visual and 40% text. This was due to me having too much into” Student

“finding specific information about my topic”

Others found it

difficult to come up with focus questions:

Student C. “It was difficult to come up with the

questions to start the assignment”.

Student B. “To pick a topic”

Student E. “Working out which questions I should find

research for”

Many students

reported some of the information literacy skills both easy and difficult. This

contradiction can be understood when examining excerpts such as the following:

Student A. “If I’m interested, I will find reading and

memorising some key points really easy”. This remark was categorised under

“Understanding and applying information”, as it entails deriving meaning from

information. The same student wrote “I find note taking really hard.” This was

categorised as “difficulty with accessing information as it entailed

difficulties with choosing the correct information from a wide array of

information. It was also categorised under “Understanding and applying

information”, as it entailed figuring out what was appropriate for the topic.

Student B made

comments demonstrating self-insight and organisational skills under both

Questions 4 and 5. For Question 4 she reported, “For me, I find it easy to take

notes on paper because I can easily get distracted on the computer”. For

Question 5 she put, “I find it hard to concentrate on the computer”.

Figure 12: Tasks deemed as difficult to do when conducting research

In

the second and third questionnaire a question appeared asking students about

their feelings regarding their research. The question was not asked in the

first questionnaire. Half way through

the inquiry task only three student of the sample of 10 felt confident about

their research and knew where they were heading. The rest of the students

reported either feeling overwhelmed or confused. These sentiments were

reflected by the cohort as whole although very few students reported feeling “frustrated”.

This response is to be expected at this stage of an inquiry task. Once students

have started researching they often find the enormous amount information

available confusing and struggle to determine what is relevant, appropriate or

true. It is at this stage that intervention from the instructional team is

often required. Once they have started to master the topic and have presented their

findings there is often an improvement in their feelings about the topic. This

can be seen in the following graph comparing student feeling at the mid-way

point to the end point of their inquiry task.

Figure 13: Students' feelings about their research mid-way through the task as compared to the end of the task

As

can be seen from the above graph all except one student either improved in

affect or stayed the same. Only Student C remained unhappy about her work.

In

Question 6 of Questionnaire 3 the students are asked “What did you learn in

doing this research project?”

Although

many of the students assumed this to be a repetition of Question 1 “Write down

what you know about this topic” there were many others that reported gains in

self-insight such as:

Student

A. “I learnt that I need to take good

notes from information and then turn it into good, well-structures paragraphs.

I also learnt that time management is

vital”.

Student

C. “I have to learn to manage my time

before I start the project. I learnt that I need to complete all work when I

can and as soon as I can. I learnt I need to prioritise”

Student

D “researching for valid information is not extremely easy”

Student

E. “To start research early. Making sure

to create a bibliography as I went. To not trust all websites. That some

information is just opinion. Focusing on the assignment. Time management.”

Student

F. “ I need to work on not doing this at

the last minute. I learnt that writing more notes and studying about my topic

helps me present my topic better and makes it seem that I know a lot of stuff

on litter”

Student

H. “ ...if I focus and concentrate hard

I will complete a task, despite the due date. I also learnt that you have to

have very good time management for a big research task like this as well as any

other assignment or task” Student I. “I learnt to be organised and to make sure I

keep up to date with my research and journal.”

Student

J. “I learnt about myself as a

researcher that I am good at finding lots of general information, however

sometimes I have trouble finding specific information about my topic. I also

learnt that some websites are biased or have incorrect information”

Figure 14: Self reported skills attained by the inquiry task

As

can be seen from the graph, responses that rated highly for this question were

“Understanding and applying information” as well as “improvement strategies”;

these were mentioned by over half of the students. Organisational skills were also mentioned by a

third of the students. These were identified as problem areas for many students

in the previous 2 questionnaires. This shows that tutorials presented by the

instructional team paid off and that students will be better equipped to excel

at this type of inquiry task in future.

References

Kuhlthau, C., Maniotes, L., & Caspari, A. (2007). Guided Inquiry: Learning in the 21st Century. Westport, Connecticut: Libraries Unlimited

References

Kuhlthau, C., Maniotes, L., & Caspari, A. (2007). Guided Inquiry: Learning in the 21st Century. Westport, Connecticut: Libraries Unlimited

Todd, R. J.,

Kuhlthau, C. C., & Heinstrom, J. E. (2005). School library impact

measure (SLIM): A toolkit and handbook for tracking and assessing student

learning outcomes of guided inquiry through the school library. Center for

International Scholarship in School Libraries, Rutgers University.

No comments:

Post a Comment